The Federal Child Tax Credit: Effects on Child Poverty

By: Jimmy Ragan

The expansion of the child tax credit (CTC) and its monthly distribution as part of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) from July 2021 until the conclusion of monthly payments in December 2021 reduced child poverty levels. The CTC expansion was not renewed in 2022, and child poverty has risen back to pre-expansion levels. This backgrounder summarizes the complicated history of the CTC and explores three policy alternatives to reduce child poverty rates: 1) making the 2021 CTC expansions permanent, 2) converting the expanded CTC into a child allowance, and 3) expanding affordable early childcare.

History of the Child Tax Credit

The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 passed a $400 nonrefundable CTC per child, which increased to $500 in 1999, for families making under $110,000 or $75,000 for single or head of household filers. The subsequent Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 introduced incremental increases in the CTC until it reached $1,000 in 2010. This act also made a portion of the credit refundable, called the additional child tax credit (ACTC), which allowed many low-income families to receive the credit as a refund if they made at least $10,000. These increases did not stay incremental: the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 and the Working Families Tax Relief Act of 2004 instituted the $1,000 credit right away.

Some changes in refundability rate calculations were made throughout the next 13 years, but the Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in late 2017 substantially increased the amount per child. This act doubled the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 and increased the refundable ACTC from $1,000 to $1,400 per child. It also increased the income levels eligible for the credit from $110,000 to $400,000 for families and from $75,000 to $200,000 for single or head of household filers. However, the TCJA restricted eligibility by requiring SSNs of all children for whom the CTC was claimed: previously, an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) had been sufficient to claim the credit.

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred congressional action to help families who were struggling. The ARP Act of 2021 temporarily raised the CTC from $2,000 to $3,600 for children 5 or younger and to $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17. The previous minimum income threshold for claiming the ACTC was eliminated and the cap on the refundable portion of the credit was removed, making the 2021 CTC fully refundable. These increases were phased out at $150,000 for married filers, $112,500 for head of household filers, and $75,000 for single filers. To provide immediate relief, these credits were delivered in advance of tax file returns. The ARP reverted to TCJA levels at the end of 2021.

President Biden recommended the expansion to the CTC be made permanent in his Build Back Better American Families Plan, but Congress did not include the CTC expansion in their 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

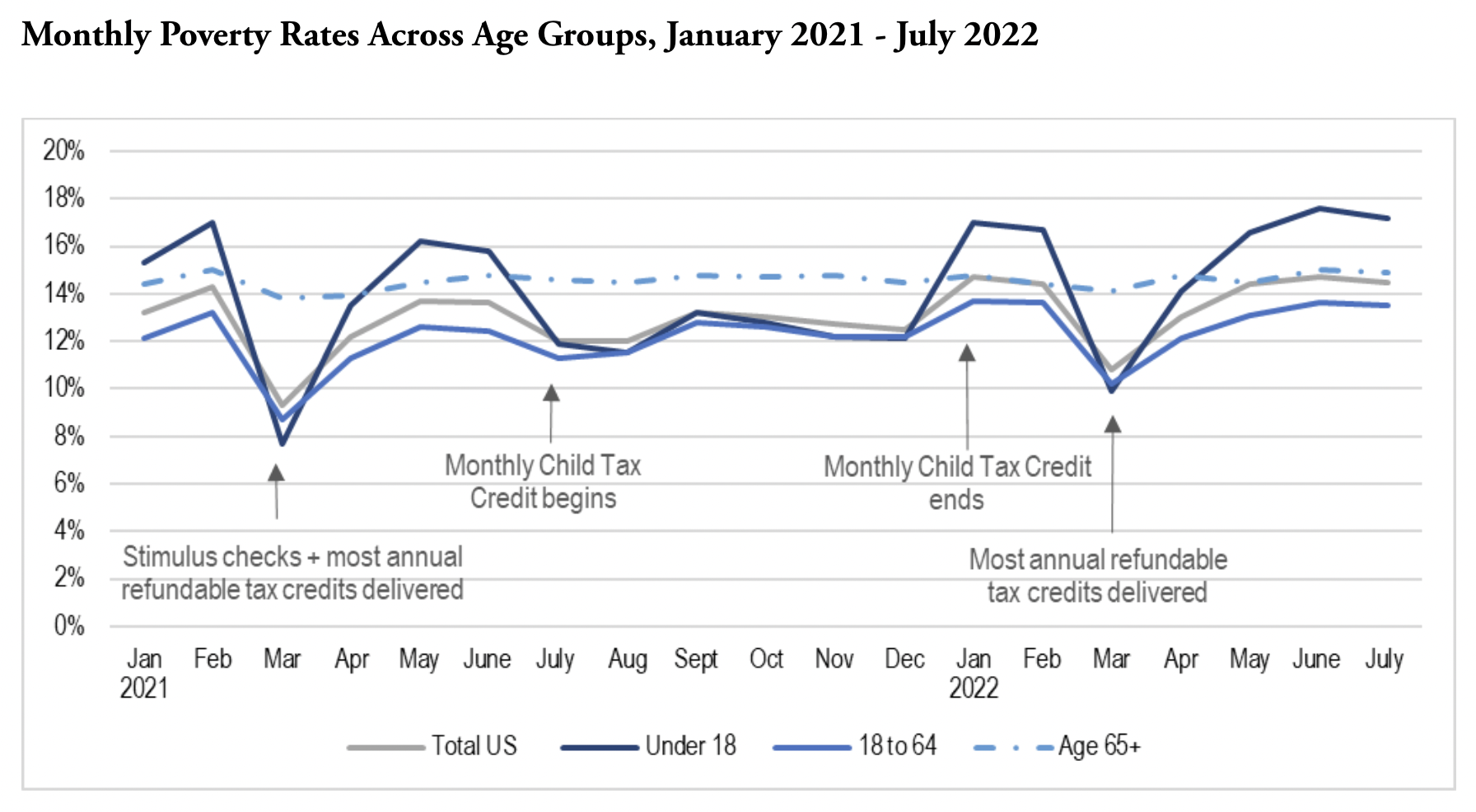

Recent Increases to Child Poverty

The July 2022 child poverty rate was 17.2%, 5.3 percentage points higher than the rate of 11.9% in July 2021. One significant source of supplementary income was available to low-income families in July of last year that is absent this year: the advance expanded CTC. The child poverty rate also jumped from 12.1% in December 2021 to 17% in January 2022, which coincided with the end of the advance CTC payments. The relationship is clear: the expanded CTC lifted millions of children out of poverty and sent many back under the threshold absent the monthly payments.

This comes at a time when price inflation is historically high. Food, a basic human necessity, increased 8.9% from January to July of 2022, very high compared to a historical average of 1.7% in the first seven months of years 2001 to 2020. The combination of higher prices and loss of supplemental income is concerning for current and future child poverty levels.

Recent Poverty and the CTC

Congress wrote the current CTC into law in 2017 and expanded its reach during COVID-19 relief in 2021, but both were written as temporary measures. The 2021 expansion expired on December 31, 2021, and the 2017 CTC expires after 2025. With no laws in place to make permanent the recent CTC increases and expansions, families without income have already lost eligibility. And, come 2026, qualifying families will see their CTC shrink by more than half.

Current CTC law also limits eligibility via identification criteria. Through 2025, for a child to be claimed for a CTC, they need to have a valid Social Security Number (SSN), leaving many law-abiding taxpayers with ITINs for their children unable to benefit from the credit. Although this policy will expire in a few years, the current inaccessibility of this credit to taxpayers with dependents who don’t have SSNs excludes some families who had benefited before 2017.

Policy Alternatives to Reduce Levels of Child Poverty

Codify the CTC Expansion as Permanent Law

One way to reduce child poverty is to make the expanded CTC permanent law. The measures put in place by the ARP targeted low- and middle-income families, including those who previously did not meet the minimum income threshold for a refundable credit. Sunsetting the more restrictive identification requirements put in place by the TCJA would also extend CTC eligibility to more families currently living in poverty. Congress entertained several proposals and amendments, but no action has passed both chambers of Congress.

Provide Qualifying Families with a Child Allowance

Another way to distribute assistance to families in need is through a child allowance. This allowance sidesteps the format of the CTC and instead gives low- and middle-income families a small stipend to offset extra costs associated with raising children. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) conducted an analysis of the effects of a near-universal child allowance equal to the maximum CTC levels under the ARP using quasi-experimental models for comparison. NBER determined the net benefit to society was $982 billion in terms of future health, earnings, and social outcomes.

Expand Affordable Early Child Care

Lower- and middle-income families are also served through affordable access to early childcare. Over 35% of the median income for a single parent is spent on center- or home-based childcare using the national average price of $10,174. A report by the Center for American Progress highlighted the uncertain future of federal Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) funding. Much like it temporarily expanded the CTC, the ARP increased CCDBG funding to help support low-income families; the measure expires in 2024. The report recommends 1) the expansion of CCDBG applications to both new and existing providers so more locations can access funding, 2) greater engagement with local resource and referral agencies to better support providers, 3) an increase to current CCDBG reimbursement amounts to better account for the true cost of care so child care facilities don’t refuse to offer services to children eligible for CCDBG, and 4) a commitment to supply-building activities and quality rating systems by all states receiving CCDBG funding.

A Clear Solution to Child Poverty Met with Congressional Inaction

We are likely to see another temporary expansion or extension in the next few years with the TCJA expiring at the end of 2025, but a permanent law change has not yet garnered majority support. Alternatives for fighting child poverty have floated around the legislative agenda, such as affordable early childcare and an additional monthly child allowance, but neither have reached a floor vote since the Build Back Better plan. The policy window for addressing the CTC is still open, but mid-term election power shifts will likely dictate which versions of the CTC are passed into temporary or permanent law.

Jimmy Ragan (he/they) is a MPP '24 focused on education and social policy.